Starving artists have been affected by more than just piracy and streaming royalties

Intheir many (justified) laments about the trajectory of their profession in the digital age, songwriters and musicians regularly assert that music has been “devalued.” Over the years they’ve pointed at two outstanding culprits. First, it was music piracy and the futility of “competing with free.” More recently the focus has been on the seemingly miniscule payments songs generate when they’re streamed on services such as Spotify or Apple Music.

These are serious issues, and many agree that the industry and lawmakers have a lot of work to do. But at least there is dialogue and progress being made toward new models for rights and royalties in the new music economy.

Less obvious are a number of other forces and trends that have devalued music in a more pernicious way than the problems of hyper-supply and inter-industry jockeying. And by music I don’t mean the popular song formats that one sees on awards shows and hears on commercial radio. I mean music the sonic art form — imaginative, conceptual composition and improvisation rooted in harmonic and rhythmic ideas. In other words, music as it was defined and regarded four or five decades ago, when art music (incompletely but generally called “classical” and “jazz”) had a seat at the table.

When I hear songwriters of radio hits decry their tiny checks from Spotify, I think of today’s jazz prodigies who won’t have a shot at even a fraction of the old guard’s popular success. They can’t even imagine working in a music environment that might lead them to household name status of the Miles Davis or John Coltrane variety. They are struggling against forces at the very nexus of commerce, culture and education that have conspired to make music less meaningful to the public at large. Here are some of the most problematic issues musicians are facing in the industry’s current landscape.

1. The Death of Context

Digital music ecosystems, starting with Apple’s iTunes, reduced recordings down to a stamp-sized cover image and three data points: Artist, Song Title, Album. As classical music commentators have long argued, these systems do a poor job with composers, conductors, soloists and ensembles. Plus, as I argued at length in a prior essay, they’re devoid of context. While there are capsule biographies of artists and composers in most of the services, historic albums are sold and streamed without the credits or liner notes of the LP and CD era. The constituency of super-fans who read and assimilate this stuff is too small to merit attention from the digital services or labels, but what’s lost is the maven class that infuses the culture with informed enthusiasm. Our information-poor environment of digital is failing to inspire such fandom, and that’s profoundly harmful to our shared idea about the value of music.

2. Commercial Radio

It’s an easy target, but one can’t overstate how profoundly radio changed between the explosion of popular music in the mid 20th century and the corporate model of the last 30 years. An ethos of musicality and discovery has been replaced wholesale by a cynical manipulation of demographics and the blandest common denominator. Playlists are much shorter, with a handful of singles repeated incessantly until focus groups say quit. DJs no longer choose music based on their expertise and no longer weave a narrative around the records. As with liner notes, this makes for more passive listening and shrinks the musical diet of most Americans down to a handful of heavily produced, industrial-scale hits.

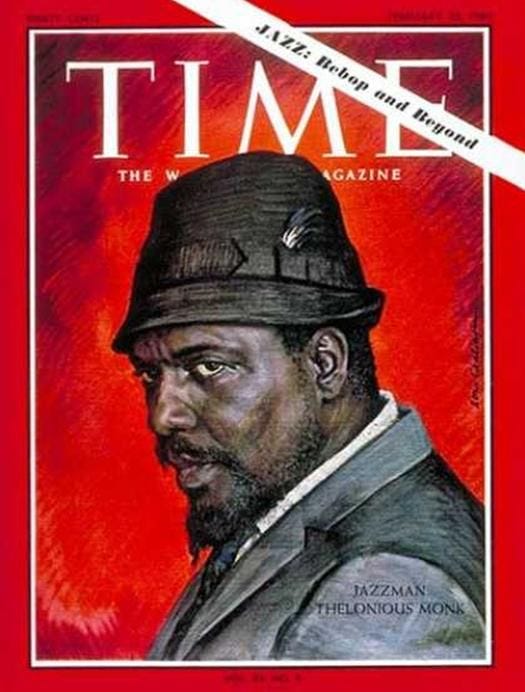

3. The Media

In the 1960s, when I was born, mainstream print publications took the arts seriously, covering and promoting exceptional contemporary talents across all styles of music. Thus did Thelonious Monk wind up on the cover of TIMEmagazine, for example. When I began covering music for a chain newspaper around 2000, stories were prioritized by the prior name recognition of the subject. Art/discovery stories were subordinate to celebrity news at a systemic level. Industry metrics (chart position and concert ticket sales) became a staple of music “news.” In the age of measured clicks the always-on focus grouping has institutionalized the echo chamber of pop music, stultifying and discouraging meaningful engagement with art music.

4. Conflation

A little noticed but corrosive quirk of the digital age is the way our interfaces conflate music with all other media and entertainment choices. iTunes started it by taking software ostensibly for collecting and playing music and morphing it into a platform for TV, film, podcasts, games, apps and so on. This is both a symbol and a cause of the dwindling meaning and import of music in the multi-media onslaught that is our culture. The shiny displays distracting people away from “just” music are already ubiquitous. So why impose them on a music player? I believe that one reason vinyl and phonographs are hot again is that musically oriented people crave something of a shrine for their music — a device that is for music only.

5. Anti-intellectualism

Music has for decades been promoted and explained to us almost exclusively as a talisman of emotion. The overwhelming issue is how it makes you feel. Whereas the art music of the West transcended because of its dazzling dance of emotion and intellect. Art music relates to mathematics, architecture, symbolism and philosophy. And as such topics have been belittled in the general press or cable television, our collective ability to relate to music through a humanities lens has atrophied. Those of us who had music explained and demonstrated to us as a game for the brain as well as the heart had it really lucky. Why so many are satisfied to engage with music at only the level of feeling is a vast, impoverishing mystery.

6. Movies & Games

We as a culture do hear quite a lot of “classical” or composed instrumental music, but it has migrated from the concert hall to the video game and movie score. On one hand, that’s given young composers options to make a living, and some very good music is being imagined for these imaginary landscapes. But there’s a pernicious effect of the ubiquitous media sound track, in that whole galaxies of musical ideas and motifs and moods have been essentially occupied and rendered cliché. How does a young person steeped in the faux-Shostakovich rumbling of a war game soundtrack hear real Shostakovich and think it’s any big deal? This is rarely remarked on, but I believe that thousands of cumulative impressions of background music assigned to “romance” and “grief” and “heroism” have laid down layers of scar tissue on our ability to feel something when tonal symphonic music is made or written in the 21st century.

7. Music in Schools

It all begins — or ends — here. Like any other language, the rules and terms and structure are most readily absorbed by the young. And as music’s been cut from more than half the grade schools in the US in a long, grinding trend, the pushback has been based increasingly on evidence about music education’s ripple effects on overall academic performance — the ‘music makes kids smarter’ argument. This is true and vital, but we tend to lose sight of the case for the value of music in our culture — that music education makes kids more musical. Those who internalize music’s rules and rites early in life will be more likely to attend serious concerts and bring a more astute ear to their pop music choices as adults.

Those who care about the future of the music business ought to spend less time complaining about digital disruptions and expend more energy lifting up the public’s awareness of serious music, because we truly do devalue music when we reduce our most impactful art form to an artifact of celebrity and a lifestyle choice. Complex instrumental music has become marginalized to within an inch of its very existence, and that has a lot to do with industry folk defining “value” in only the way that affects their mailbox money.

No comments:

Post a Comment